Today is the anniversary of one of many incidents of White people and soldiers attacking and killing Native men, women and children. This anniversary is of the Wounded Knee Massacre, December 29, 1890.

In the late nineteenth century, Indian “Ghost Dancers” believed a specific dance ritual would reunite them with the dead and bring peace and prosperity. On December 29, 1890, the U.S. Army surrounded a group of Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee Creek near the Pine Ridge reservation of South Dakota.

Wounded Knee Massacre, American-Indian Wars

During the ensuing Wounded Knee Massacre, fierce fighting broke out and 150 Indians were slaughtered. The battle was the last major conflict between the U.S. government and the Plains Indians.

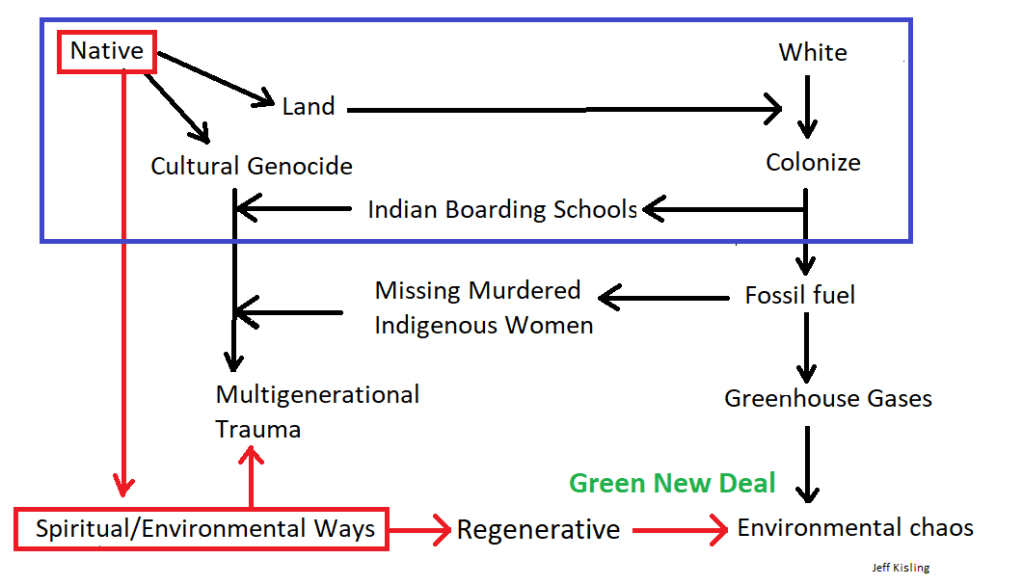

By the early 20 century, the American-Indian Wars had effectively ended, but at great cost. Though Indians helped colonial settlers survive in the New World, helped Americans gain their independence and ceded vast amounts of land and resources to pioneers, tens of thousands of Indian and non-Indian lives were lost to war, disease and famine, and the Indian way of life was almost completely destroyed.

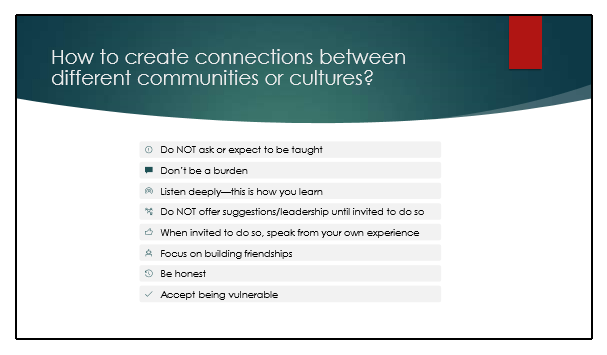

Following is an abbreviated summary of many different acts against native peoples. I include this because the first step in healing and reconciliation is to acknowledge the wrong that was done. In my experience almost no White people have any concept of these things.

Stacie Martin states that the United States has not been legally admonished by the international community for genocidal acts against its indigenous population, but many historians and academics describe events such as the Mystic massacre, The Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre and the Mendocino War as genocidal in nature. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz states that US history, as well as inherited Indigenous trauma, cannot be understood without dealing with the genocide that the United States committed against Indigenous peoples. From the colonial period through the founding of the United States and continuing in the twentieth century, this has entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories, forced removal of Native American children to military-like boarding schools, allotment, and a policy of termination. The letters of British commander Jeffery Amherst indicated genocidal intent when he authorized the deliberate use of disease-infected blankets as a biological weapon against indigenous populations during the 1763 Pontiac’s Rebellion, saying, “You will Do well to try to Inoculate the Indians by means of Blanketts, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execreble Race”, and instructing his subordinates, “I need only Add, I Wish to Hear of no prisoners should any of the villains be met with arms.” When smallpox swept the northern plains of the U.S. in 1837, the U.S. Secretary of War Lewis Cass ordered that no Mandan (along with the Arikara, the Cree, and the Blackfeet) be given smallpox vaccinations, which were provided to other tribes in other areas.

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations, among others in the United States, from their homelands to Indian Territory in eastern sections of the present-day state of Oklahoma. About 2,500–6,000 died along the Trail of Tears.[92] Chalk and Jonassohn assert that the deportation of the Cherokee tribe along the Trail of Tears would almost certainly be considered an act of genocide today. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the exodus. About 17,000 Cherokees, along with approximately 2,000 Cherokee-owned black slaves, were removed from their homes. The number of people who died as a result of the Trail of Tears has been variously estimated. American doctor and missionary Elizur Butler, who made the journey with one party, estimated 4,000 deaths.

Genocide of indigenous peoples

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of a known cholera epidemic, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, following the Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830, 8,000 Cherokee died, about half the total population.

During the American Indian Wars, the American Army carried out a number of massacres and forced relocations of Indigenous peoples that are sometimes considered genocide. The 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, which caused outrage in its own time, has been called genocide. Colonel John Chivington led a 700-man force of Colorado Territory militia in a massacre of 70–163 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho, about two-thirds of whom were women, children, and infants. Chivington and his men took scalps and other body parts as trophies, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia.

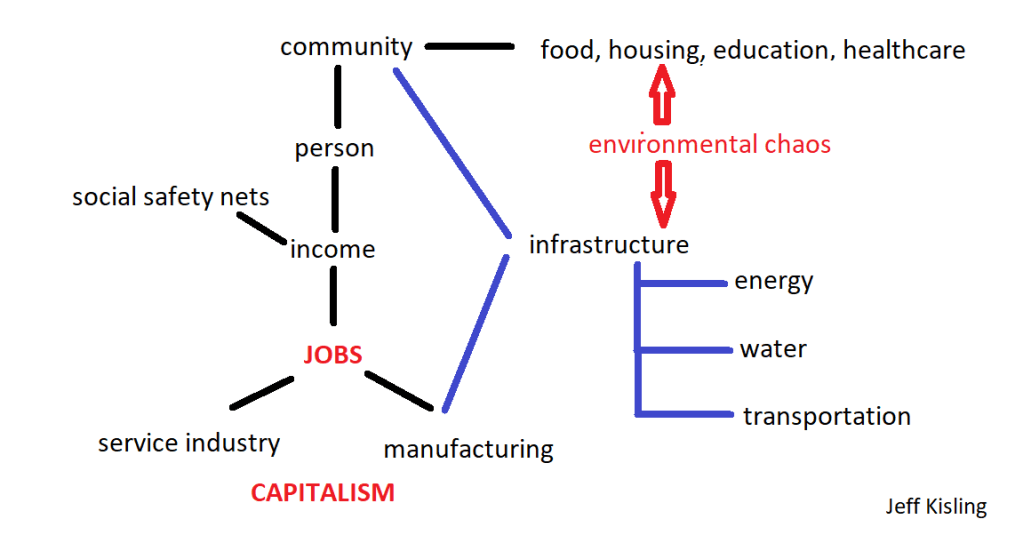

The conflict, oppression and deaths continue. The preceding history provides context for modern oppression and targeting of native peoples. The trauma from that history has passed from generation to generation.

And the violent oppression continues. An example is this recent article in The Guardian: “Exclusive: Canada police prepared to shoot Indigenous activists, documents show” by Jaskiran Dhillon in Wet’suwet’en territory and Will Parrish, December 20, 2019.

Canadian police were prepared to shoot Indigenous land defenders blockading construction of a natural gas pipeline in northern British Columbia, according to documents seen by the Guardian.

“Exclusive: Canada police prepared to shoot Indigenous activists, documents show” by Jaskiran Dhillon in Wet’suwet’en territory and Will Parrish, December 20, 2019.

Notes from a strategy session for a militarized raid on ancestral lands of the Wet’suwet’en nation show that commanders of Canada’s national police force, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), argued that “lethal overwatch is req’d” – a term for deploying snipers.

The RCMP commanders also instructed officers to “use as much violence toward the gate as you want” ahead of the operation to remove a roadblock which had been erected by Wet’suwet’en people to control access to their territories and stop construction of the proposed 670km (416-mile) Coastal GasLink pipeline (CGL).

In a separate document, an RCMP officer states that arrests would be necessary for “sterilizing the site”.

Wet’suwet’en people and their supporters set up the Gidimt’en checkpoint in December 2018 to block construction of the pipeline through this region of mountains and pine forests 750 miles north of Vancouver.

On 7 January, RCMP officers – dressed in military-green fatigues and armed with assault rifles – descended on the checkpoint, dismantling the gate and arresting 14 people.

This video by Nahko and JOSUE RIVAS includes video from Standing Rock showing military force used against praying women, children and men.

Native children continue to this day to be forcibly removed from homes and usually placed with non-native people. This is a continuation of the same practices used in the past to forcibly remove native children from their homes, to attend boarding schools in attempts to assimilate them into White culture with traumatic results, including death. See this blog post about a native home for native children: https://kislingjeff.wordpress.com/2019/12/14/a-place-to-call-home/

Native peoples continue to be present to protect Mother Earth. The epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) is associated with the “man camps” at the pipeline construction sites.